Over the past 18 months of COVID lockdowns, many of us have experienced the heaviness of loneliness — missing family, friends, and meaningful social contact.

But even before the pandemic, loneliness was a daily experience for almost 20% of older Australians, particularly those over 75.

Being older does not mean being lonely. Loneliness can affect us all. But it disproportionally affects older people living alone or in aged care facilities, and whose health issues limit their social interaction.

Loneliness increases an older person’s risk of illness, from cardiovascular diseases to dementia.

The older people we spoke to for our research also talked openly about how devastating loneliness can be. As Scarlett* explains:

You get teary for the want of human company.

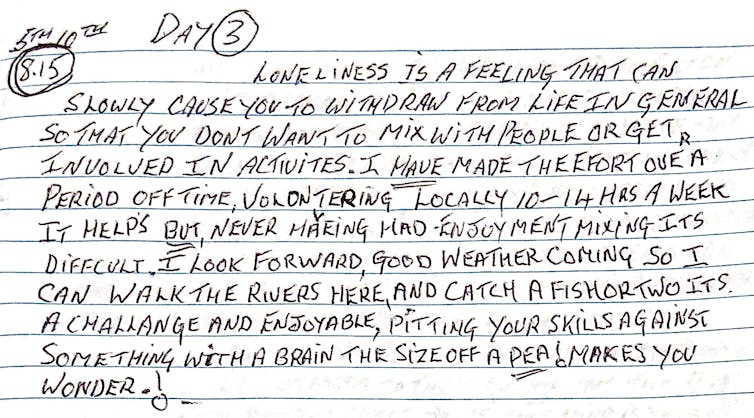

Yet, the success of initiatives to tackle loneliness has been limited by the complexity of loneliness, the stigma around it and the diversity of people’s situations in later life.

Listening to older people

We know loneliness is a serious social and health issue. So, what can those experiencing loneliness tell us and what are their suggestions for addressing it?

During two lockdowns in 2020, we explored these questions with 35 Victorians aged 65 and above who were living alone. We used a combination of interviews, surveys and diary-keeping.

What changed with COVID?

Before COVID many participants felt lonely in the morning or evening, but during lockdowns, they felt it throughout the entire day.

On top of the isolation of lockdown, the restrictions disrupted their regular coping strategies such as “keeping busy”, volunteering, engaging in community activities or clubs. As Scarlett noted:

With COVID, the strategies that one puts in place to try to deal with loneliness have ceased to be, not by choice but necessity.

Jacko similarly explained the only people he had contact with were shop assistants.

You must understand that, for me, lonely is the norm. Pre-COVID, I would get some respite by going out on activities, but the lockdown has killed all of them.

What helps?

Despite the disruption to their usual strategies, most participants sought other options during lockdowns.

Maintaining social contact, through calls with loved ones or via small daily interactions, was vital. While for most, communication via technology was not the same as meeting in-person, video calls and emails eased their loneliness. Online activities with grandchildren, including gaming or assisting with homework, made them feel included and needed.

But technology only helped ease loneliness if it wasn’t used for superficial contact. Short video calls, for example, were not enough. Many hoped technology would not encourage loved ones to reduce visits after lockdowns. As Lisa explained:

Technology is not my favourite means of communication. You miss out on small nuances in body language and spontaneity on phoning or video conferencing.

Although small talk was insufficient to fully tackle loneliness, daily interactions with neighbours, passersby and supermarket staff took on greater importance during lockdowns. Some would go to specific shops because staff would chat to them.

Other helpful strategies were having a well-defined routine and going for walks. Planning enjoyable things they could do on their own, such as painting or gardening, and appreciating “small things” outside in nature, during a walk, gave participants a sense of purpose.

What older people want others to know about loneliness

The older people in our study had three key messages about their experience.

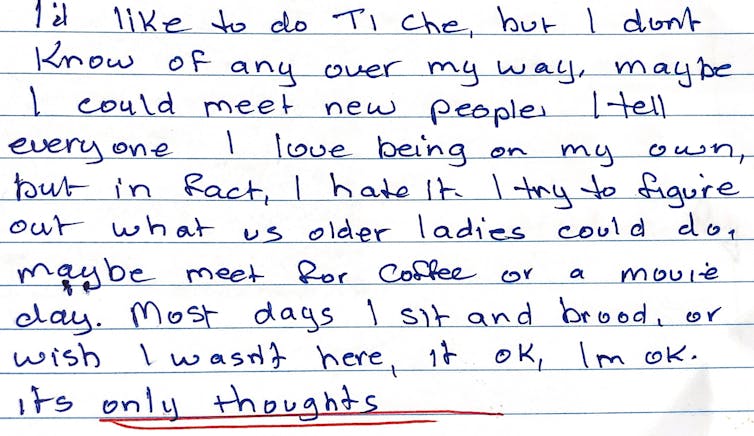

The first was, admitting to feeling lonely is not easy, especially for older people living alone. They want to remain independent and not be seen as a failure. As June wrote in her diary:

I tell everyone I love being on my own, but in fact, I hate it.

Second, many waited for their phone to ring to break the silence. A house can seem like a prison when you can’t leave it. As Fred told us:

Loneliness kicks in as silence descends on the home.

Third, the lonelier you feel, the more rejected you feel by family, the community and society at large. Our participants started believing no-one cared about them and even reported suicidal ideation. As Bob wrote:

who wants anything to do with an old-age pensioner regarded as unproductive, invalid, good-for-nothing-old-man, parasite on the community?

This sentiment was made worse by the way older people were portrayed during the pandemic as either disposable or too vulnerable.

Pick up the phone

Our research suggests if we don’t initiate conversations with our older friends and family members about loneliness, it is unlikely they will mention it.

It also shows older people already put a lot of effort into managing their loneliness. But they could do with more help from the rest of us.

We know that simple things, such as picking up the phone for a meaningful chat, or planning another routine interaction, are incredibly important. Not only do they improve the quality of older people’s lives, they could be life saving as well.

*Pseudonyms have been used.

If this article has raised issues for you or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or beyondblue on 1300 22 46 36.

This piece was produced as part of Social Sciences Week, running 6-12 September. A full list of events can be found here. Barbara Barbosa Neves will appear in a webinar “Emotion inequality in pandemic Australia” at 11am, Wednesday September 8.![]()

Barbara Barbosa Neves, Senior Lecturer in Sociology, Monash University; Alexandra Sanders, Sociology Research & Teaching Associate, Monash University; David Colón Cabrera, Lecturer in Anthropology, Monash University, and Narelle Warren, Associate Professor in Sociology and Anthropology, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

USD

USD  AUD

AUD  CAD

CAD  NZD

NZD  EUR

EUR  CHF

CHF  GBP

GBP